Modern societies are experiencing a widespread trend toward weight loss. This is a response to one of today’s greatest pandemics—obesity—and to the increasing awareness of its negative health consequences. According to World Health Organization (WHO) data, in 2022 one in eight people worldwide lived with obesity (BMI > 30), amounting to nearly one billion individuals. Obesity is not only a disease in itself but also contributes to the development of many other serious conditions, such as cardiovascular diseases, type 2 diabetes, and even cancer. As early as around 400 BCE, Hippocrates observed that people with obesity were at higher risk of sudden death. Paradoxically, on a global scale, more people die from excess food consumption and related diseases than from malnutrition. So what can be done to counteract obesity?

From various sources—often far removed from scientific reasoning—we are offered new diets or nutritional regimes. Diets based solely on fats or carbohydrates, high-fiber diets, light diets, skipping breakfast or dinner, eating only within a designated time window, fasting every other day, and so on. Aside from the side effects that accompany some of these diets, the results of such weight-loss efforts are generally insufficient, and it is particularly difficult to maintain lower body weight in the long term. Despite scientific advances, the most effective method for achieving lasting weight reduction in the treatment of obesity remains bariatric surgery, which in simple terms involves reducing the size of the stomach. Recently, much hope has been placed in antidiabetic medications used to treat obesity—the so-called GLP-1 receptor agonists—which prepare the body for glucose intake and suppress appetite. However, their use is still in its early stages, and only the future will show whether they are fully safe.

Why is it so difficult to lose weight? The answer lies in the evolution of our brain. We must remember that for most of human existence, our brain evolved under conditions entirely different from those we experience today. This pertains primarily to the constant availability of high-calorie foods, sedentary lifestyles, and pervasive chronic stress. To understand how our brain once functioned—and still does (the agricultural revolution occurred only about 10,000 years ago)—we must look at the lives of our hunter-gatherer ancestors. They faced frequent food shortages; therefore, hunger dominated over satiety and triggered the active search for food.

Moreover, whenever food was plentiful—for example, after hunting an animal—the body switched into a mode of maximizing fat storage. Lastly, although stress among early humans could be intense, it was generally short-lived. Today, chronic stress typically leads to harmful metabolic changes. To achieve long-term weight loss, we must therefore overcome at least three systems in our brain: the hunger–satiety system, the reward system, and the stress-response system, all of which are specialized for activities opposing weight reduction and the loss of energy reserves. It is also important to note that the diet of early humans did not combine simple sugars (honey, fruit) with fats (hunted game or fish)—a combination that is now present in almost every meal and significantly accelerates weight gain.

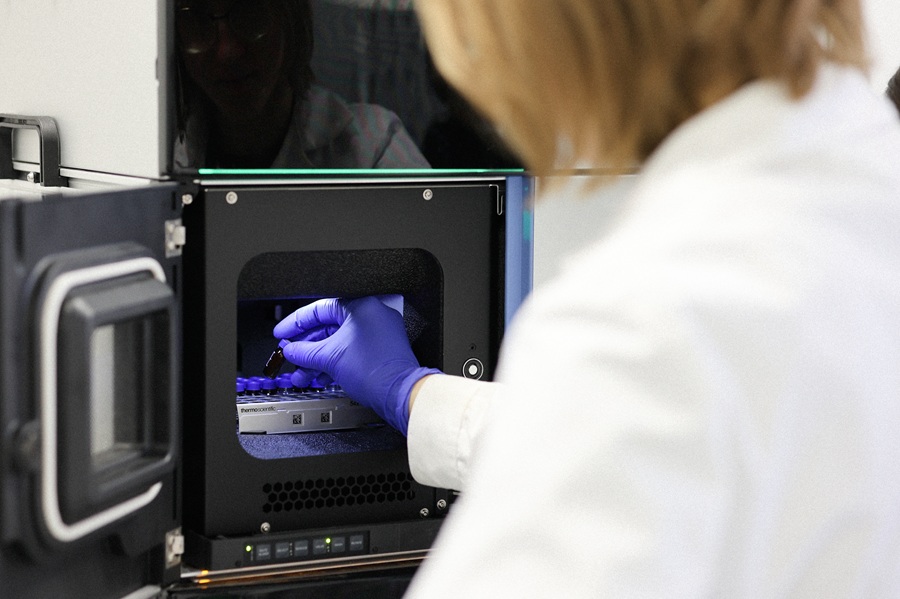

These are exactly the kinds of issues—namely, how the brain regulates our eating behaviors in the context of both neuropsychiatric disorders such as anorexia and conditions like obesity—that are studied by the Neuroplasticity and Metabolism Research Group at the Łukasiewicz Research Network – PORT Polish Center for Technology Development, led by Dr. hab. Witold Konopka.