Psychiatric diagnostics still relies primarily on conversations with a physician—but this may soon change. As part of the SAME-NeuroID project, researchers have developed unified research protocols (SOPs) that enable modeling of mental disorders at both the cellular and behavioral levels. This is a step toward objective diagnostic tests that could transform the treatment of depression, schizophrenia, or PTSD.

Today, diagnosing mental disorders depends on a clinical interview—subjective, shaped by a physician’s experience and the patient’s ability to describe symptoms. Treatment itself is often based on trial and error. This is likely one of the reasons why it is still easier for many to acknowledge thyroid or gastrointestinal disease than depression or anxiety disorders diagnosed by psychiatrists.

Meanwhile, a recent European Commission report shows that 46% of Europeans experienced a mental-health problem (e.g., depression) within the past 12 months (2023 data). Only half of them sought help from a specialist.

Tests that can objectively detect biological changes in individuals with depression would offer an opportunity not only for improved diagnostics and more precise treatment selection, but also for a societal shift in how mental health is perceived.

A Common Research Language for Mental Disorders

Scientists at Łukasiewicz – PORT have developed a set of unified research protocols—SOPs—that allow laboratories around the world to model mental disorders in a standardized way at the cellular and behavioral levels. Put simply: they created and validated instructions enabling laboratories to reproduce features of psychiatric conditions in exactly the same way. Why does this matter?

“We cannot perform experiments on the living human brain, so scientists recreate its environment—cells, their connections, and disease mechanisms—in the lab. The problem is that everyone does it differently, and we cannot be certain that we are obtaining comparable results,” explains Dr. hab. Witold Konopka, leader of the SAME-NeuroID project.

Although SOPs may sound like academic paperwork, they are fundamentally practical tools:

“To progress toward clinical trials and ultimately diagnostic tests for disorders such as depression, we must ensure that research conducted in different laboratories is reproducible, comparable, and scalable. Only then can we speak of global research on the mechanisms underlying psychiatric disorders, on biomarkers that signal disease development, and on therapies tailored to individual patients,” Dr. Konopka emphasizes.

From Skin Cells to a ‘Mini-Brain’

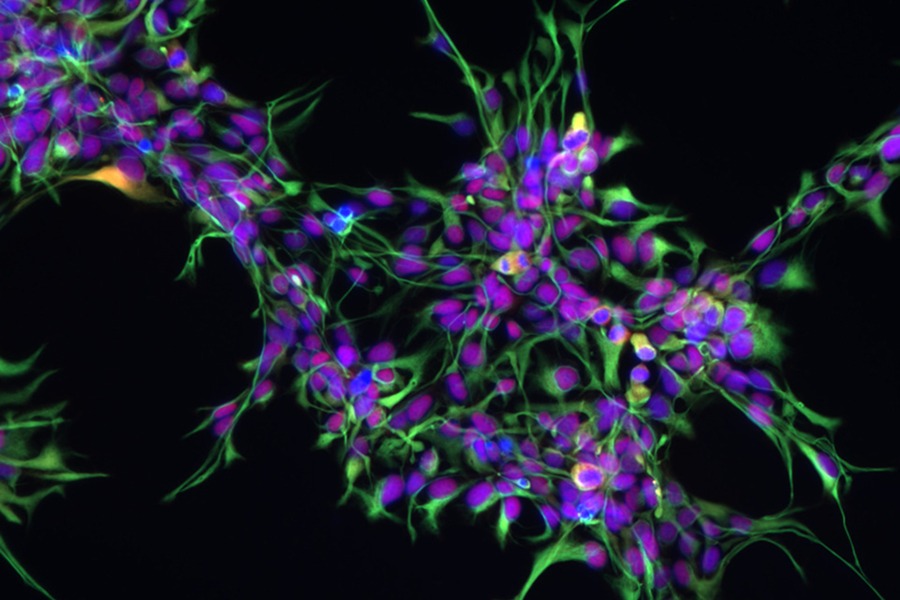

At Łukasiewicz – PORT, research begins with reprogramming adult skin or blood cells into induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), which can transform into any cell type in the body. These cells preserve the patient’s genetic code—including hereditary conditions, risk variants associated with mental disorders, and individual biological traits influencing brain function. This means that even though experiments are conducted in vitro, they reflect aspects of the patient’s biology.

From iPSCs, researchers generate neurons, astrocytes, and brain organoids.

• Neuronal networks allow scientists to study disruptions in communication occurring in depression or schizophrenia.

• Astrocytes, once considered merely support cells, are gaining prominence. Researchers at Łukasiewicz – PORT investigate genes such as FKBP5, a regulator of stress resilience. Dysregulation of FKBP5 specifically in astrocytes leads to prolonged and intensified stress responses, increasing the risk of depression, PTSD, schizophrenia, and neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease.

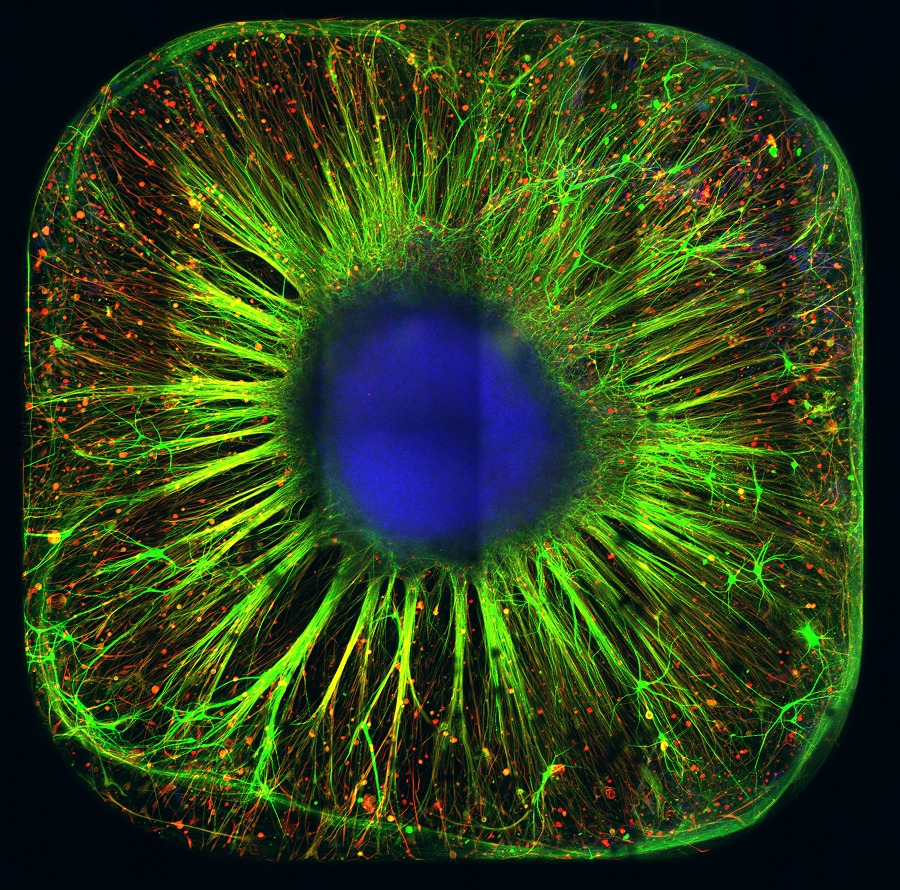

• Organoids—three-dimensional “mini-brains”—mimic the architecture of developing brain tissue, enabling the study of autism, advanced disease modeling, and complex drug testing in a setting far more brain-like than traditional cell cultures.

Organoid grown in the laboratory of the Neurodegeneration Mechanisms Research Group at Łukasiewicz – PORT

Complementing the cellular work, in-vivo studies focused on how chronic social stress (e.g., exposure to an aggressor) affects brain activity, behavior, and molecular pathways. Artificial intelligence detects depression-like symptoms in animals after only a few days of severe stress, eliminating subjective assessment and accelerating detection of behavioral changes indicative of disease or therapeutic response.

Contributors to the development of this new diagnostic platform include Dr. hab. Witold Konopka, Dr. Michał Ślęzak, Dr. Michał Malewicz, Dr. Agnieszka Krzyżosiak, Dr. hab. Tomasz Prószyński, Dr. Bartosz Zglinicki, Dr. Ewa Mrówczyńska, and Dr. Bertrand Dupont.

Reproducibility of the Łukasiewicz – PORT SOPs was validated in partner laboratories: Erasmus University Medical Center (Rotterdam), Max Planck Institute of Psychiatry (Munich), and ICM Institute for Brain and Spinal Cord (Paris).

A Step Toward New Diagnostics

The platform developed at Łukasiewicz – PORT is not yet a diagnostic test—but it is the first real step toward one. It enables scientists to observe, quantify, and compare what was previously unmeasurable.

“This is also a significant technological advancement that positions us at the forefront of modern psychiatric research,” says Dr. Konopka. “It led to additional grants, including a €15 million Horizon Europe Teaming for Excellence project. We also initiated collaboration with industry—this platform is ready for use in preclinical, clinical, and industrial research.”

The goal is not to replace psychiatrists, but to equip clinicians and patients with tools that support diagnostics and effective treatment. In a world where global health organizations warn of the alarming decline in mental health—especially among children—where WHO ranks depression as the leading cause of disability worldwide, and where depression contributes to nearly 800,000 suicides every year, new solutions based on genetic, cellular, and behavioral data are urgently needed.

This data-driven, transdiagnostic approach is also strongly supported by the European Union. Under its Comprehensive Approach to Mental Health, the EU invests in projects aligned with RDoC (Research Domain Criteria), integrating data from multiple domains to better understand mechanisms of psychiatric disorders.

SAME-NeuroID is an international project carried out at Łukasiewicz – PORT from 2022–2025, funded by the European Union.

Its primary goal was to develop unified SOPs for modeling neuropsychiatric disorders at the cellular and behavioral levels, enabling depression, schizophrenia, and PTSD research to be reproduced and compared across laboratories worldwide.

The project also included:

• intensive training for young researchers,

• knowledge exchange among partners in France, Germany, and the Netherlands,

• educational activities for academia and industry,

• communication initiatives raising public awareness about innovation in mental health.

Project partners: ICM Institute for Brain and Spinal Cord (Paris), Max Planck Institute of Psychiatry (Munich), and Erasmus University Medical Center (Rotterdam).

The symposium “European Networking for Brain Research,” summarizing project achievements, accompanied the 17th Congress of the Polish Society for Neuroscience, held on September 2–5, 2025 in Wrocław.